Faithfulness and truth meet; justice and well-being kiss. Truth springs up from the earth; justice looks down from heaven.

–Psalm 85:11-12

122 years ago this month, a former soldier, reviled by his countrymen and abandoned by all except for his family and a few loyal friends, embarked on a ship for South America. His destination: Îsle du Diable, or Devil’s Island, a harsh and barren rock off the coast of French Guyana. Sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement, he had no reason to believe he would ever see his loved ones or his country again.

The man’s name? Alfred Dreyfus, at that time the highest ranking Jewish officer in the French army at the end of the 19th century. Accused of espionage for the Kaiser’s Germany and convicted of treason, Dreyfus’ case quickly became a cause célèbre, galvanizing the forces of anti-Semitism in France in unprecedented ways, even as Dreyfus also became a rallying cry for a group of French intellectuals, such as writers Anatole France, Marcel Proust, and Emile Zola, who believed in his innocence.

The man’s name? Alfred Dreyfus, at that time the highest ranking Jewish officer in the French army at the end of the 19th century. Accused of espionage for the Kaiser’s Germany and convicted of treason, Dreyfus’ case quickly became a cause célèbre, galvanizing the forces of anti-Semitism in France in unprecedented ways, even as Dreyfus also became a rallying cry for a group of French intellectuals, such as writers Anatole France, Marcel Proust, and Emile Zola, who believed in his innocence.

There is no question that in 1895 the French Army was rife with anti-Semitism; without knowing this it would be impossible to fully understand the events which unfolded around Alfred Dreyfus. According to historians such as Oxford University’s Ruth Harris, author of Dreyfus: Politics, Emotion, and the Scandal of the Century, Dreyfus’ accusers, conditioned by their anti-Semitism, were inclined to suspect him as the culprit from the get-go. Rather than intentionally framing a man they knew to be blameless, the military prosecutors were predisposed to view ambiguous evidence as proof of guilt, while dismissing facts pointing toward his innocence or reinterpreting them to support their preconceptions.

What followed, then, shouldn’t surprise anyone . . . . Two experts testified that the writing on the espionage documents somewhat resembled Dreyfus’ handwriting; three others concluded the penmanship belonged to someone else, but latter’s testimonies were ignored. After Dreyfus’s arrest, investigators thoroughly searched his files and home, but found nothing. In the mind of his accusers, however, this only proved how resourceful a spy he was; it demonstrated his skill at destroying evidence. In interviewing his teachers at the École Polytechnique, the elite military academy Dreyfus attended, the prosecutors learned he had excelled in foreign languages and was remembered for having a prodigious memory, which only furthered their belief in his guilt — after all, language proficiency and good memory are clearly traits beneficial to spies.

Nearly a century and a quarter later, it’s easy for to shake our heads at such flimsy evidence and its power to convince otherwise intelligent individuals of an innocent man’s guilt. Yet before we become too smug, are we really so different? When convinced of our own rectitude, we tend to magnify any evidence that supports our view, while discounting anything that contradicts our conclusions. The term for this is “motivated reasoning”: it explains why when a foul is called by a referee against our team, we protest and jeer the call, but should something identical happen to the opposing squad, we’re likely to believe it a good call, while deriding the other side’s fans for having sour grapes.

A week ago, President Trump issued an executive order banning travel for 90 days from seven Muslim-majority countries. The same order closed the door for 120 days to all refugees, regardless of country, including those who had been vetted and had valid visas; and barred entry to Syrian refugees indefinitely.

Supporters claim that thanks to the President’s executive order, America is safer today. But is that factually true? The second, third, and fourth highest exporters of terror to the world — Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan — aren’t covered at all by Trump’s ban. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia, the country of origin for the 9/11 attacks is also missing from the 7 nation list. And, in case you were wondering how many have died on American soil at the hand of terrorists from these seven banned countries . . . between 1975 and today the answer is zero.

Ilhan Omar, elected to the Minnesota Legislature, came to America when she was a child as a Somali refugee granted legal asylum

Fact: there is no group more vetted and scrutinized by the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security than refugees — not once they arrive, but up to 24 months before they are given permission to depart for the U.S. Fact: since the 1970s, only three Americans have been killed on U.S. soil by individuals granted legal asylum — killed by by refugees from Castro’s Cuba. According to a study of the Cato Institute, a think tank founded by the conservative billionaire Koch brothers, the chance of any one of us being killed by a refugee is 1 in 364 billion in a given year — about 20,000 times higher than the odds of being struck dead by lightning.

These are not opinions, they aren’t “alternative” facts. Yet to those who are convinced that refugees are a great threat, all of the above will be dismissed as “biased’ or with an impatient “Yes, but . . .” as if facts are of secondary importance to opinions.

Of course, motivated reasoning can be found everywhere. It explains the lynching of thousands of innocent African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries on the flimsiest evidence imaginable; it underscores the skepticism expressed by those who reject the reality of climate change, not because the science is shaky, but because it doesn’t sit well with the outcome they desire; it highlights the spurious claim that millions of illegal aliens voted in the 2016 elections, despite the dearth of any evidence. Time and again we see instances of motivated reasoning in which truth is the handmaiden of opinion, rather than the other way around. Nor is it limited to one end of the political spectrum: when a respected civil rights leader in Congress calls the Chief Executive an “illegitimate President” — despite the fact that the latter won the Electoral College fair and square — he does what those who sought to delegitimate President Obama with the claim he wasn’t born in the U.S. did . . . the total absence of proof to the contrary.

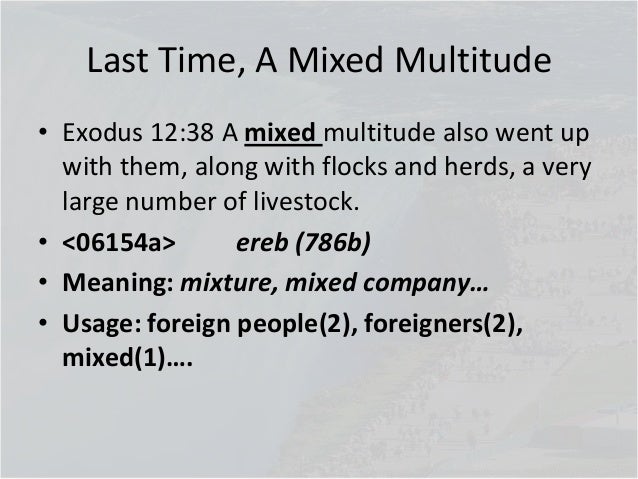

In Parshat Bo, this week’s Torah portion, the text underscores the broad character of the Exodus from Egypt. Moses did not limit those leaving Egypt to the groups most likely to agree with his decisions or least likely to challenge his leadership. The Torah states, “וְגַם־עֵ֥רֶב רַ֖ב עָלָ֣ה אִתָּ֑ם — A mixed multitude came out of Egypt with the Israelites” (Exodus 12:38). According to the rabbis the “mixed multitude” consisted of non-Israelites who were themselves oppressed and had made common cause with the Israelites. Apparently they were not insignificant in number — In Mekhilta, a midrashic work on the book of Exodus, Rabbi Yishmael claims they numbered 180,000. Rabbi Akiva goes so far as to maintain they added up to 240,000 persons — equal in number to more than 1/3 of the male Israelite population of 600,000. That the rabbis could envision Moses enabling the mixed multitude to join the Israelites, despite the likelihood of becoming oppositional (a likelihood which came to pass), says a great deal about a willingness to accept diversity, not just in the abstract, but in reality.

In Parshat Bo, this week’s Torah portion, the text underscores the broad character of the Exodus from Egypt. Moses did not limit those leaving Egypt to the groups most likely to agree with his decisions or least likely to challenge his leadership. The Torah states, “וְגַם־עֵ֥רֶב רַ֖ב עָלָ֣ה אִתָּ֑ם — A mixed multitude came out of Egypt with the Israelites” (Exodus 12:38). According to the rabbis the “mixed multitude” consisted of non-Israelites who were themselves oppressed and had made common cause with the Israelites. Apparently they were not insignificant in number — In Mekhilta, a midrashic work on the book of Exodus, Rabbi Yishmael claims they numbered 180,000. Rabbi Akiva goes so far as to maintain they added up to 240,000 persons — equal in number to more than 1/3 of the male Israelite population of 600,000. That the rabbis could envision Moses enabling the mixed multitude to join the Israelites, despite the likelihood of becoming oppositional (a likelihood which came to pass), says a great deal about a willingness to accept diversity, not just in the abstract, but in reality.

This is a valuable lesson to remember. More and more, those on either end of the political spectrum seek out like-minded folk only, using their shared views to reinforce one another’s convictions. Listen to talk radio, and you’ll find that invariably only those who agree with the host’s basic premise are given unfettered access to echo the sentiments of the loyal. True, every so often an individual representing the opposing view is given a minute or two to speak, but s/he is invariably cut off by the host or shut down with rhetoric and ridicule. Letting the other guy open his mouth functions only as a kind of prop, a foil to show the faithful what jerks the other guys are.

To quote George Orwell in his novel of distopia, 1984: “For, after all, how do we know that two and two make four? Or that the force of gravity works? Or that the past is unchangeable? If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable, what then?”

But this is surely not the Jewish way. The Talmud teaches in the name of Rabbi Hiyya Bar Rav: ‘”And the people stood with Moses from morning until evening” (Exodus 18:13). Does it make sense that Moses judged the people all day long? When did he learn his Torah? Rather, the Torah comes to teach us that any judge who judges with truth for even an hour is seen as though he had partnered with God in the creation of the world. Here [in Exodus] it is written: “And the people stood with Moses from morning until evening.” while there [in Genesis] it is written: “And there was morning and there was evening, one day”’ (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 10a). To equate truth-based decision-making with the creation of the world itself underscores its indispensability to the existence of a moral society.

Ultimate knowledge belongs to God alone, but neither have we been deprived of the ability to apprehend truth — truth that is neither convenient nor inconvenient, but simply is. Those of small mind and smaller heart will dig in and hunker down in defensiveness and rationalization in the face of truth. There remains, however, something noble and powerfully righteous in the person who is either curious enough or brave enough to want to see the landscape as it is, not as he wills it to be; to consider the cold facts and dare to say, “Perhaps I need to rethink my position.”

The true hero of the Dreyfus story was a Lieutenant Colonel named Georges Picquart. He didn’t have a higher opinion of Jews than his brother officers; like most of them, he initially assumed Dreyfus was guilty. But Picquart was different in one regard. After Dreyfus’ conviction, as a counter-intelligence specialist he had reason to believe the espionage on Germany’s behalf was still happening. He even came across new spy letters whose handwriting appeared to match perfectly the documents that had sent Dreyfus to Devil’s Island. When he brought this information to his superiors, they could neither fathom their own culpability in sending an innocent man to prison nor accept that the Jew Dreyfus might actually be innocent. Instead, they fantastically insisted that Dreyfus must have trained another spy to write in a similar hand so that if the one were caught the other might escape.

Picquart didn’t like Jews, but he did believe in fairness, justice and truth. Because of his desire to see the truth prevail, Picquart was punished by being relieved and sent to duty in the remote desserts of Tunisia, and was even imprisoned for a time. Yet in the end his dogged pursuit of the truth set Alfred Dreyfus free.

Oddly enough, that Georges Picquart was suffused with the same anti-Semitic prejudices of his time and class is part of the story’s moral. Unlike his fellow officers, he did not allow his beliefs to cloud his judgment: his beliefs did not determine the facts, but the facts did determine his view of Dreyfus’ likely innocence.

We don’t need more leaders capable of insisting they’re right no matter what the facts are; those who, in the fact of contradictory evidence, simply shout more loudly or insult more vehemently. What we desperately need are leaders capable of being wrong and admitting it, leaders sufficiently secure and self-assured to believe they can change their mind when confronted by evidence, without losing face or being unworthy of public respect. We would be a better country and a society were our leaders willing on occasion to stand up and say, “I felt very strongly about a particular policy, but after much reflection, consultation with experts of varying perspectives, and a careful review of the facts, I have come to believe that my initial assessment was wrong.”

Yet to merit such leadership, we cannot expect less from ourselves. Aldous Huxley, author of yet another distopian novel, Brave New World, reminds us of a foundational truth in all societies worthy of respect “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” Except in Orwellian nightmares, 2 + 2 will still be equal to 4 . . . no matter what anyone else says.